|

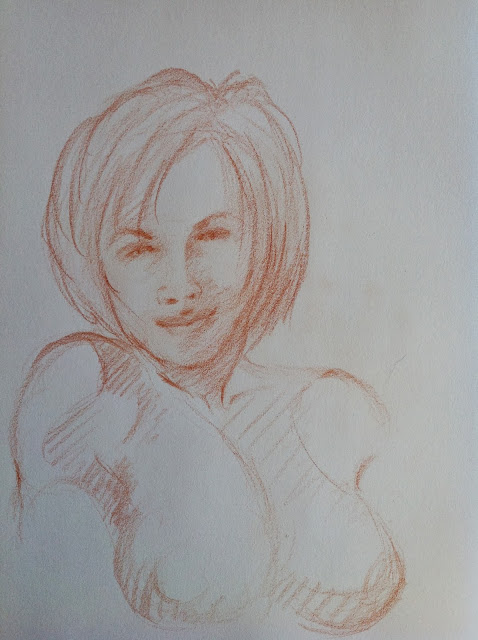

| Raphael Santi. Study for Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1510. Red chalk. |

|

| Raphael Santi. Study for Massacre of the Innocents. |

|

| Raphael Santi. Study for Massacre of the Innocents. |

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

(Robert Frost.)

In my

last post, I touched on the subject of deliberate practice, and since that time I have been asked why my drawings are confined to nudes; no clothed figures.

The answer is that I always draw with a purpose, I never doodle; my practice is deliberate. I struggle with the question of whether greatness requires talent or hard work or both. And here is the problem: no one really knows. So my tactic has been to make a commitment, work hard, and see where it leads me.

Drawing the human form has long been considered the ultimate challenge for a draftsman. The human body's complexity of interconnected forms - which change their appearance immensely with changes in point of view, lighting, exertion, gravity, and numerous other factors - offer a mind-numbing amount of information.

Artists have risen to this challenge for thousands of years. The Greeks elevated the nude form to incredible heights in the 2nd century BC and artists, ever since, have considered mastery of the nude form as a rite of passage. And, once the nude has been mastered, any other drawing challenge will pale in comparison.

I believe that all clothed figures should begin with an understanding of the nude, just as all nudes should begin with an understanding of gesture; as the body is revealed through the surface of drapery, so is the body the veil through whose surface is revealed the soul.

To draw the figure convincingly, the artist must

understand the form (see my

previous post on drawing well). Then the figure may be draped in clothing and still retain believable volume and dimensionality. Note in the above studies, by Raphael, that he has begun his figures as nudes before adding the drapery.

I believe that deliberate practice - and, by this, I mean focused, persistent attention to the subject under study

to the exclusion of all else - is the only way to achieve mastery of a subject, even when the concept of

talent is considered. So, in respect to drawing the human form, it means drawing the nude figure obsessively, for years, until every aspect of the form is internalized and the figure can be drawn from any point of view, in every aspect in three dimensional space, from imagination.

So, be mindful of

how you practice, as well as how

often you practice: practicing a skill ten thousand time

incorrectly will never lead to improvement and will actually be detrimental to improvement. This is where a frequent, honest assessment of your progress is critical. This can be done by yourself, if you are honest with yourself, or, better still, by a competent teacher or master draftsman.

I have been drawing the nude figure, seriously, for over two years now. I believe that I have made progress along the path upon which I set out, but, like Frost's traveler in his poem

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, I, too, have miles to go before I sleep.